Lower back pain and Parkinson’s disease

Lower back pain is an extremely common problem in the general population, as well as for people with Parkinson’s disease (PD). It tends to make moving more difficult, adding to the challenges of PD. Tim Nordahl, PT, DPT, a physical therapist at Boston University gave an excellent presentation as part of APDA’s Let’s Keep Moving Webinar Series. Because this is such a prevalent issue, and because there are things you can do to help alleviate your back pain, I wanted to summarize and highlight this important topic.

Causes of lower back pain

People with PD may have the same lower back issues that affect the general population.

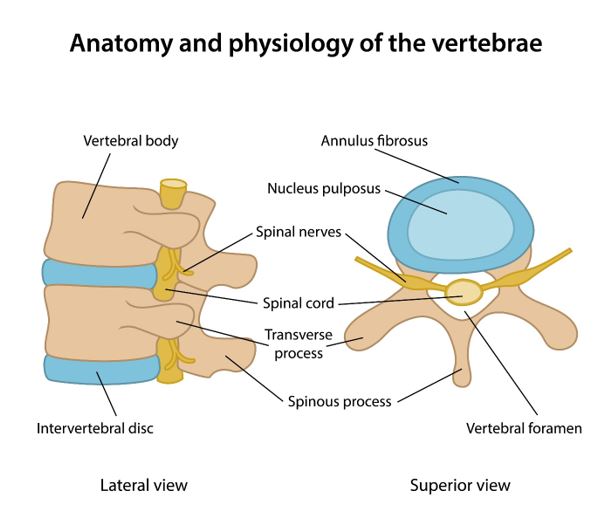

Here is a picture of the spine and its surrounding structures.

There are specific structural problems of the lower spine that can lead to pain. Primarily the structural problems fall into two categories:

- Narrowing of the central spinal canal through which the spinal cord travels. This can cause spinal stenosis and typically manifests as pain with standing or walking that improves with bending forward or sitting.

- Narrowing of the exit holes through which the spinal nerves travel. This can cause what is known as radiculopathy, pinched nerve, or sciatica and typically manifests as pain that travels down a leg.

There are many causes of these narrowings including:

- Arthritis – Swelling of the joints (or contact points) between the structures in the spine. Arthritis can be caused by normal wear and tear or less commonly by an inflammatory or auto-immune condition.

- Bone spurs — Bony projections that develop along bone edges can occur where bones meet and are associated with arthritic changes in the spine.

- Herniated disc – the blue area in the picture above is the intervertebral disc – a cushion between each vertebral body. There is a soft substance in the middle of the disc called the nucleus pulposus that can push through the outer core and can compress the hole through which the spinal nerves travel.

- Compression fracture – a vertical collapse of the vertebral body, often caused by osteoporosis or thinning of the bones.

Much less common, are infections of the spine or cancers growing around the spine. Both of these conditions can push on the spine or spinal nerves and cause pain.

Surprisingly, all of these causes together typically account for a small percentage of lower back pain. For most people with lower back pain, no specific structural cause can be identified.

Lower back pain in people with Parkinson’s

In a previous blog, we discussed pain and PD in general and highlighted different types of pain that a person with PD might experience.

PD contributes factors that can cause or worsen lower back pain, such as rigidity (stiffness) of the trunk muscles or dystonia (abnormal muscle contractions caused by PD or PD medications) of the trunk muscles. Both rigidity and dystonia can fluctuate with medication timing and correlate with ON and OFF time.

In addition, PD can be associated with central pain, which is poorly understood and thought to be due to abnormalities in the brain itself. Some new research suggests that PD can change how the brain feels pain – that the loss of dopamine can make pain feel worse or make a person more likely to feel pain.

We know that:

- there is a higher prevalence of lower back pain in people with PD vs aged-matched controls

- certain features of PD such as increased age, depression, rigidity, and stooped posture are associated with lower back pain

- lower back pain can make it harder to deal with the challenges of PD because it is associated with lower activity levels. This can breed a vicious cycle in which lower back pain leads to decreased activity levels and then lower activity levels conspire to make the lower back pain worse

Evaluating lower back pain

When a person develops lower back pain, a neurological history and exam can help rule out serious medical conditions that may need further evaluation and intervention. The neurological history will collect information about other neurological symptoms such as numbness, tingling, weakness, new bowel or bladder symptoms, etc. The neurologic exam will assess strength, sensory changes and reflexes, among other things, which can shed light on spine function and help determine if a serious medical condition is present. Lower back pain caused by a serious medical condition is rare (e.g. infections around the spine, cancer around the spine). Nevertheless, be sure to tell your neurologist about any new symptoms that you may have.

For most people, neurologic history and exam will confirm that lower back pain can be managed conservatively. When this is the case, treatment of the pain with exercise and physical therapy is the best course forward. Your neurologist may determine that imaging of the lower back will be helpful. If that is the case, he/she may order an MRI of the lower spine. An MRI will show structural changes to the lower spine but will not visualize PD-specific causes of lower back pain such as rigidity, dystonia, or central pain.

Studies have shown that MRIs can reveal structural changes that do not result in pain at all. So, it is important not to let imaging be the sole guidance of lower back pain management.

What are the potential treatments for lower back pain?

Once serious medical conditions have been ruled out, the focus can turn to reducing pain and improving quality of life. There are multiple strategies to managing lower back pain in the context of PD.

Physical therapy

Exercise and physical therapy (PT) are usually the first lines of treatment to try and often can result in a noticeable improvement. A physical therapy evaluation will determine what type of exercises are likely to be most beneficial for your specific back pain. Manual manipulation may also be performed, which is when the physical therapist uses their hands to put pressure on muscle tissue and manipulate joints in an attempt to decrease back pain. It is recommended that you find a physical therapist who has experience with Parkinson’s and therefore more familiar with the PD-specific challenges you may be dealing with.

A physical therapy assessment will analyze patterns of movements and their association with pain and will work on impaired posture and impaired walking patterns that can exacerbate back pain. A physical therapist, for example, may prescribe exercises to increase hip flexibility, and improve core strength which can improve posture. Improving walking patterns may also be a focus of physical therapy. Many of the exercises will be done at your appointment with your physical therapist, but you will also be given exercises to continue on your own at home and these are an essential part of the healing process.

Getting started with PT while in pain is difficult, but necessary. Your PT will be mindful of this and ease you into an exercise regimen. In some cases, for example, certain causes of lower back pain cause more pain when standing or walking and this type of pain may be more manageable if exercises are performed in a pool.

APDA has resources to help. Our Be Active and Beyond book, available for free in English and Spanish, demonstrates exercises that can help improve hip flexibility and core strength to improve lower back pain.

If you have questions about exercise or physical therapy or want a referral to a physical therapist with expertise in PD, you can contact the APDA National Rehabilitation Resource Center either by phone (888-606-1688) or email (rehab@bu.edu) for advice.

Treat OFF time

As discussed above, dystonic pain and pain due to rigidity can fluctuate with medication timing and therefore may be able to be treated by adjusting the timing and dosage of medications. You can learn about ways to treat OFF time by watching one of our webinars on the topic.

Occasionally, non-dystonic pains can also be an OFF phenomenon and can improve with a dose of levodopa. People with PD who have pain in this pattern are said to have “non-motor OFFs”. These patients, in addition to, or instead of, having fluctuations of their motor symptoms in response to PD meds, have fluctuations in non-motor symptoms, which could include pain, depression, or anxiety. If pain occurs in this way, it can often be treated by adjusting medications to minimize the OFF time.

Treat depression

Depression is a very common non-motor symptom in PD – with pain and depression closely linked. Depression can contribute to chronic pain and chronic pain can lead to or increase depression.

Sometimes treatment of depression can alleviate an element of the pain, so an evaluation of depression is definitely warranted when trying to figure out how to treat chronic pain in PD. Talk to your neurologist about getting a referral to a psychiatrist who can do a proper assessment, and if appropriate prescribe treatment. Treatment plans for depression may include psychotherapy (such as cognitive behavior therapy) and/or medication, as well as other treatment options.

Complementary treatments for back pain

Massage therapy and acupuncture are two complementary treatments that are often used for pain. There have been small studies investigating the use of massage therapy and acupuncture for motor symptoms of PD, but more studies are necessary to s determine if they specifically help with PD pain. You can also view a Q+A about complementary treatments in PD.

Other treatments of lower back pain

NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) which include medications such as ibuprofen and naproxen, as well as acetaminophen, can be very beneficial for pain in PD, as they are for the general population. These medications do not typically have neurologic side effects, so they are well tolerated in people with PD. They can have other side effects though, so as always, discuss all medications that you are taking, including over-the-counter medications, with your doctor. If these medications do not provide sufficient back pain relief, your doctor may prescribe a pain medication. In addition, he/she may refer you for a procedure such as an epidural injection to help with lower back pain. Rarely, surgery may be recommended if a specific structural reason for pain is identified.

Tips and Takeaways

- There are many causes of lower back pain. However, for many people (with and without PD), no specific cause can be identified

- Rarely, lower back pain can be caused by a serious medical condition. Therefore, evaluation of new lower back pain by a neurologist is important

- Features of Parkinson’s disease such as rigidity, dystonia, and central pain can contribute to lower back pain

- Management of lower back pain often involves exercise and physical therapy focused on strengthening core muscles, improving posture, improving walking patterns, and increasing activity level

- Lower back pain can also improve with better control of ON/OFF time as well as better treatment of depression

- APDA can help direct you to resources to manage your lower back pain, including our free Be Active and Beyond booklet and our National Rehabilitation Resource Center